The first step was when State Senator Norman Cutter secured a charter in 1864 for the St. Louis and Illinois Bridge Company to construct a bridge across the Mississippi River at St. Louis.

Prior to this, no bridge crossed the Mississippi River below the confluence of the Missouri River.

Steamboat Companies and railroads north of St. Louis vigorously opposed the new bridge, as did the Wiggins Ferry Company.

In 1866, a federal franchise was granted to begin construction of the bridge. However, a number of requirements were put in place. The bridge could not be a suspension bridge, it had to have a span of 500 feet, and falsework could not be used.

James B. Eads was selected as the engineer-in-chief by the St. Louis and Illinois Bridge Company in 1867. Eads was an engineer, although he has never worked on a bridge before.

He presented his concepts to the directors of the company in July of 1867, with construction to start in August of the same year.

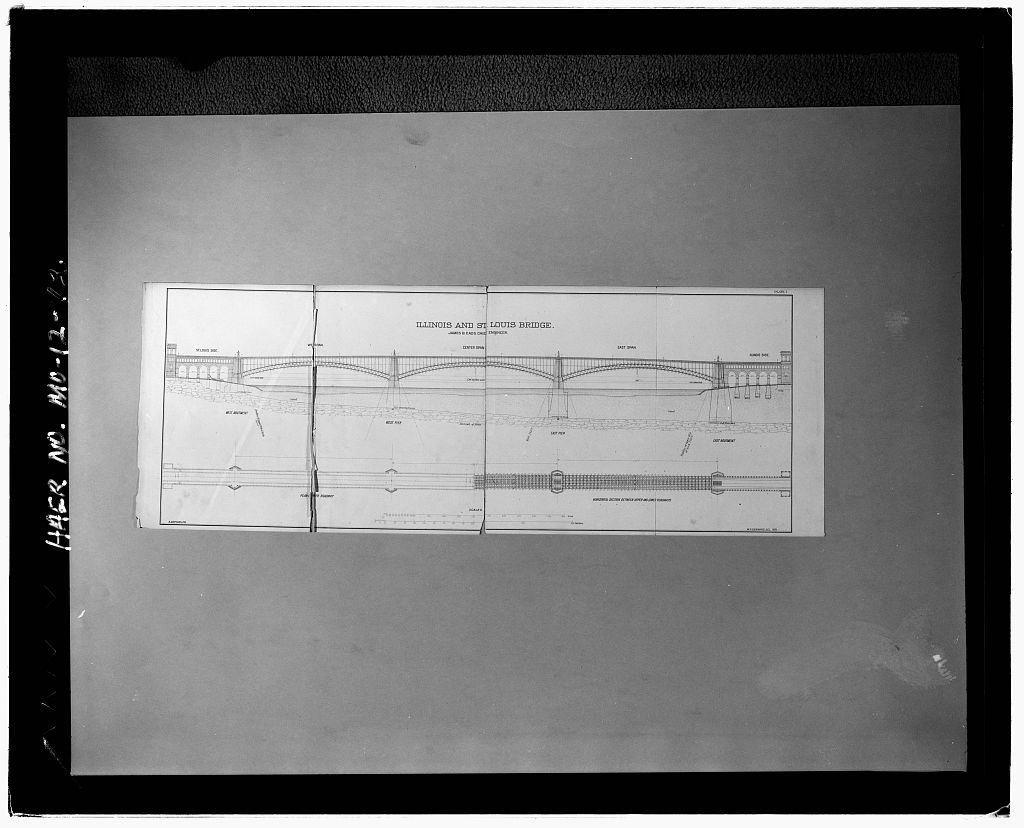

The plan Eads designed called for three steel arches, each exceeding 500 feet in length. These would be set onto stone piers founded on bedrock.

A roadway deck graced the upper portion of the bridge, and included room for four wagons, streetcars and an 8-foot sidewalk on either side.

Beneath this would lie a pair of railroad tracks.

Despite the general public support for the bridge, a rival company; known as the Illinois and St. Louis Bridge Company attempted to sabotage the efforts of Eads.

The company began by calling together a number of prominent engineers in the area to discredit Eads plans, and eventually bought newspaper advertisements attempting to undermine public support.

The rival company would be merged with the existing company in March of 1868, and Eads would go forward with his plans.

Despite a solid plan, the first of the difficulties occurred on the west abutment. Creating a watertight cofferdam proved extremely difficult due to the number of steamboat parts lying in the water.

Bedrock would be reached in February of 1868, and Eads would preside at the laying of the first cornerstone on the bedrock.

Eads would be tasked with publishing a report later that year, restoring public opinion. He referred to the bridge as an "engineering precedent." The company resumed work in May of 1868 from public work.

Eads would eventually become ill, and resign his position. The company refused his resignation. Work continued in the absence of Eads, but not as fast. This led to the company going under in September of that year.

In December of 1868, Eads returned to the United States and met with numerous bankers and railroad officials in New York. He left again for Europe in January of 1869.

The wealthy businessmen in New York refused to support any more bonds until the piers would top high water. As a result, 3 million dollars were sold in bonds.

Concurrently, Eads met with French and English engineers and came away with the concept for compressed air to construct the remaining bridge caissons. This airtight seal would allow for uninterrupted work below the river surface.

In April of 1869, Eads returned to St. Louis in good health to revise the plans, and account for the pneumatic caissons. By September, he had 1,500 men at work.

Eads also secured equipment in duplicate, including 24 boats, 37 engines, 31 pumps, 29 derricks, 40 travelers and 24 hoists.

The caissons were built by the former partner of Eads, and included pieces cut from the salvaged U.S. Ironclad Milwaukee, which sunk during the Civil War.

The stone was contracted to James Andrews of Pittsburgh, with limestone coming from Grafton, Illinois; and the granite to face the bridge coming from Virginia and Maine. Work would be seriously delayed when a pair of ships of granite sunk near Florida. Ironically, granite was discovered in Missouri.

In October of 1869, work began on the east pier. The construction reached the bedrock in February of 1870. Nearly 95 feet below the surface of the water, this was a major milestone in construction of the bridge.

At the 67 foot level, Eads brought visitors and press down; sending a telegraph to New York.

The next several months saw constant work on the east pier. For 15 days, ice cut off the pier from land. Workmen lived at the pier during this time.

The east pier was completed in January of 1870, and work on the west pier began on January 3rd of that year. Bedrock was reached by April 1st. During the summer, the pier would be completed.

A tornado in March of 1871 significantly interrupted the bridge construction. A slight redesign of the bridge included wind trusses to be added between piers.

The Bends, a condition resulting from severe compression was rampant among the bridge site. Of the 352 men in the east pier air chamber, 80 would be affected. 12 would die, and two would become paralyzed.

After 3 1/2 years, the foundations were complete and ready for steel arches. Keystone Bridge Company of Pittsburgh was contracted to provide the steel.

Per Eads standards, all parts were to be tested and be of the highest grade of metal. This was quite unusual, and set a new precedent in bridge construction.

Attaining the proper steel was found to be considerably difficult. Plans had to be revised numerous times. A tubular design of the arch was unheard of at this time, and used homogeneous steel.

American steel magnate Andrew Carnegie went to London to sell bonds. An independent engineer was proposed to review the plans. James Laurie was hired in January of 1872, but could only find small cost savings.

Because of river navigation, a typical falsework method could not be used to complete the arches. To counter this, a cantilever method was used. This imposed using wooden towers on the piers and abutments, which supported the counterweights.

In September of 1873, the west arch neared completion. Assistant engineer Colonel Henry Flad was left in charge of the bridge project.

Nearly 100 degree temperatures caused significant distortion on the final piece of the west arch. Instead of forcing it in place, it would instead be cut and a plug inserted. By December of 1873, the central and eastern two arches had connected in the middle.

Two tubes had ruptured in January of 1874, as Eads was preparing to meet with stakeholders to discuss the final funds needed to complete the project.

Eads received the news around midnight, and promptly ordered replacement tubes.

The steamboat lobby launched one final attack at the bridge in September of 1873. They claimed the bridge was not high enough. However, this was an optical illusion and the bridge was indeed high enough.

A draw span was ordered to be installed, in which Eads motioned to President Grant to drop the matter. The matter would be dropped.

On April 17th, 1874 Keystone Bridge Company announced the bridge would be open to the public the next day. However, Keystone was errored in the announcement and removed planking the next day to prevent anyone from going on it.

The bridge finally opened to pedestrians on May 24th, 1874. 15,000 persons were said to walk over the bridge. On June 3rd, 1874; the road opened to the public, and the first train crossed six days later, after General William T. Sherman ceremoniously drove the final spike into the railroad.

A fully loaded test train crossed the bridge in early July, and on July 4th, a grand spectacle unfolded at the bridge. Although President Grant was not in attendance, a 15 mile parade, many speeches and an elaborate fireworks show lit up the city. Nearly a half million people would be in attendance.

Less than five years after the bridge opened, the railroads boycotted the structure. The $10 Million structure would be auctioned off for $2 million in late 1878. Jay Gould would become owner in 1881, and leased the bridge and tunnels for 500 years to the Missouri Pacific Railroad; later to the Terminal Railroad Association of St. Louis.

The final train would cross in 1974. In 1924, the St. Louis Consulting Engineer Charles E. Smith wrote that the railroads would begin to use the MacArthur Bridge, and the City of St. Louis would come into sole possession of the Eads Bridge for commuter rail.

In 1989, this was accomplished. Currently, the Metrolink System uses the rail deck of the bridge. The road deck has been rehabilitated, and the bridge has seen significant alterations since its first appearance.

The Eads Bridge is one of the most significant bridges in the United States of America. It was one of the first bridges to use pneumatic caissons, and was the first to use a cantilevered method of construction. In addition, the tubes and replaceable components were first used on this bridge, and have since been spread to other bridges.

The spans are 200+ feet longer than any previously built. This unprecedented accomplishment was met with much praise for Eads, for whom the bridge was named.

It was listed as a National Historic Landmark in 1964, listed to the National Register of Historic Places in 1966, and was dedicated a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark in 1974.

Today, the bridge has undergone significant renovation. The Illinois Approach, originally built as a combination of girder spans for the railroad and deck trusses for the road has been replaced by a more modern structure. The Missouri Approach, featuring numerous arches of brick and stone has been altered.

Some of these arches have been sealed, and spans at 2nd and 1st Street have been replaced by steel plate girder type spans. An additional arch at the TRRA Viaduct along the west bank has also been replaced.

A tornado in 1896 also severely damaged the east approach.

Despite a seemingly infinite number of alterations, the bridge has had an incredible impact on engineering and culture. Today, the bridge is one of the most recognized landmarks in the United States.

Because of this, the author has ranked this bridge as nationally significant, the highest rating this site gives. The bridge has become a national landmark since 1874, and has carried goods and people across the Mississippi River faithfully over 140 years. This bridge should be kept intact and have minimal alterations at all costs.

However, the bridge was rehabilitated again in 2016. Arch components were replaced once again, continuing the disturbing trend of altering the work of Eads. Despite this, the bridge is still one of the most historically significant bridges in the nation.

The photo above is an overview and elevation of the structure from the west bank, looking east. To the right of the author sits the Gateway Arch, the nearby landmark in St. Louis. A number of alterations can be seen in this photo, and current construction can be seen in the foreground.

Due to the vast number of photos on this page, it has been divided into four sections. Above are overview photos, and below are the detail photos, Historic American Engineering Record Photos and Historic American Engineering Record Blueprints.

| Upstream | McKinley Bridge |

| Downstream | MacArthur Bridge (River Spans) |